Section 5: History of the Timberlake Community Club, Inc.

By Dan Reiff, October 2009

Since its inception, the Timberlake Community Club (TCC) has archived its business meeting minutes and letters of correspondence in file boxes and binders that have traveled up and down Timberlake as new officers took turns at the helm. Some of the key documents referenced in this summary have been scanned and are posted on the community website (also included in Appendix G). The paper trail recorded a timeline of events, but also revealed some insight about the neighbors who ran the organization: they were smart, efficient and dead-serious about issues that concerned neighborhood safety. Yet, they had a sense of humor and subtle wit which often jumped off the faded yellow pages.

Since its inception, the Timberlake Community Club (TCC) has archived its business meeting minutes and letters of correspondence in file boxes and binders that have traveled up and down Timberlake as new officers took turns at the helm. Some of the key documents referenced in this summary have been scanned and are posted on the community website (also included in Appendix G). The paper trail recorded a timeline of events, but also revealed some insight about the neighbors who ran the organization: they were smart, efficient and dead-serious about issues that concerned neighborhood safety. Yet, they had a sense of humor and subtle wit which often jumped off the faded yellow pages.

The process of forming the Timberlake Community Club started in the in the summer of 1950, at a picnic and informal meeting of property owners held at D.W. Barber’s house. It rained, but that didn’t dampen the spirits of the 58 neighbors in attendance representing 20 families. After dinner plates were “filled and refilled,” the group got down to business and started planning the community association. The first objectives were to appoint a charter committee for planning the organization, to join local opposition to extension of the commercial zone on Alcoa, to deal with excess money from the road-coating fund, and to inspect cleared vistas in the neighborhood.

The appointed charter committee had the following members:

O.H. Graves

Lalah Macon

Alvin Nielsen

Shirley Taylor

Wiley Bowmaster, chairman

The charter committee met several times and drafted a brief constitution and set of action items. It was determined that the organization would be required to incorporate in order to possess any assets—such as the neighborhood lot. They held a “community picnic and election” which included a formal business meeting of what would become the Timberlake Community Club on September 29, 1950, at the Bowmaster home. On the agenda was the nomination and election of the first board of directors:

Fred C. Smith, president

D.W. Barber, vice president

Wylie Bowmaster, secretary-treasurer

Shirley Taylor (O.A Graves was later appointed to replace her)

Alvin Nielsen

Over the course of the next year, the new board wrote the charter and bylaws and filed as a non-profit corporation with Knox County. The lakefront lot owned by Maloney Heights, Inc. was transferred into the neighborhood association’s possession. Efforts to get the Knox County to pave the road and the postmaster to redirect Route No. 3 along Timberlake were underway as well. Meanwhile, lots were being purchased, and families were building houses and moving in. The “first annual meeting of the Timberlake Community Club, Inc.” (TCC) was held Sunday, October 14, 1951, at the Witherspoon home. The key significance of the first meeting was the amending and approval of the By-Laws. (See Appendix D for the current amended By-Laws and Charter of Incorporation.) This first meeting also firmly established the “picnic” as the preferred venue for neighborhood meetings, a tradition which has continued for nearly 60 years.

Purpose of the Timberlake Community Club, Inc.

In 1951, the Timberlake Community Club filed the Tennessee State Charter of Incorporation “for the purpose of maintaining a club for the social enjoyment and general welfare of the Timberlake Road Community and its residents.” To fulfill that purpose, the first board of the Timberlake Community Club established a social committee, and throughout the years, various events were organized to bring neighbors together. In addition to the annual picnics and business meetings, there were annual “teas” at the Macon’s, Spring and Fall road clean-ups, and holiday parties for children at Easter, Halloween and Christmas. Adult parties were occasionally held for the grown-ups, and teenagers organized their own social events. Newsletters were created and distributed at various times to keep residents informed in between meetings and events. The duties of serving on the board and on committees were shared by members of nearly every home on the road, and the business of running the organization became another way for residents to get to know each other.

While a social agenda was the primary stated purpose, the charter also established legal provisions for enforcement of by-laws and subdivision restrictions. The incorporated status also helped provide credibility for dealing with issues that affected the neighborhood.

The appointed charter committee had the following members:

O.H. Graves

Lalah Macon

Alvin Nielsen

Shirley Taylor

Wiley Bowmaster, chairman

The charter committee met several times and drafted a brief constitution and set of action items. It was determined that the organization would be required to incorporate in order to possess any assets—such as the neighborhood lot. They held a “community picnic and election” which included a formal business meeting of what would become the Timberlake Community Club on September 29, 1950, at the Bowmaster home. On the agenda was the nomination and election of the first board of directors:

Fred C. Smith, president

D.W. Barber, vice president

Wylie Bowmaster, secretary-treasurer

Shirley Taylor (O.A Graves was later appointed to replace her)

Alvin Nielsen

Over the course of the next year, the new board wrote the charter and bylaws and filed as a non-profit corporation with Knox County. The lakefront lot owned by Maloney Heights, Inc. was transferred into the neighborhood association’s possession. Efforts to get the Knox County to pave the road and the postmaster to redirect Route No. 3 along Timberlake were underway as well. Meanwhile, lots were being purchased, and families were building houses and moving in. The “first annual meeting of the Timberlake Community Club, Inc.” (TCC) was held Sunday, October 14, 1951, at the Witherspoon home. The key significance of the first meeting was the amending and approval of the By-Laws. (See Appendix D for the current amended By-Laws and Charter of Incorporation.) This first meeting also firmly established the “picnic” as the preferred venue for neighborhood meetings, a tradition which has continued for nearly 60 years.

Purpose of the Timberlake Community Club, Inc.

In 1951, the Timberlake Community Club filed the Tennessee State Charter of Incorporation “for the purpose of maintaining a club for the social enjoyment and general welfare of the Timberlake Road Community and its residents.” To fulfill that purpose, the first board of the Timberlake Community Club established a social committee, and throughout the years, various events were organized to bring neighbors together. In addition to the annual picnics and business meetings, there were annual “teas” at the Macon’s, Spring and Fall road clean-ups, and holiday parties for children at Easter, Halloween and Christmas. Adult parties were occasionally held for the grown-ups, and teenagers organized their own social events. Newsletters were created and distributed at various times to keep residents informed in between meetings and events. The duties of serving on the board and on committees were shared by members of nearly every home on the road, and the business of running the organization became another way for residents to get to know each other.

While a social agenda was the primary stated purpose, the charter also established legal provisions for enforcement of by-laws and subdivision restrictions. The incorporated status also helped provide credibility for dealing with issues that affected the neighborhood.

Figure 4-B: Ivy at 3605 Timberlake, 2009

Some early neighborhood projects included installation of signage (street signs and address nameplates) and protection of views and vistas. Committees frequently were established to investigate various matters. An initiative in 1952 which perhaps had the most lasting visible consequence was the encouragement of neighbors to experiment with different plants to stabilize the roadside embankments. No one had yet found a suitable shrub or vine to prevent erosion. According to Margaret (Neilsen) Wayne, who grew up at 3605 Timberlake, her father, Dr. Alvin Nielsen, was likely the person who finally found something that would take root – English Ivy.

There were recurring topics addressed by the TCC over the years, and some of the major accomplishments are summarized on the following pages. Foremost always on residents’ minds was Alcoa highway. Opposition to commercial zoning expansion preoccupied early Alcoa efforts, but later agendas dealt more with safety – particularly after the highway was widened to four lanes. The background and history of the Alcoa highway development can be found in Section 6. Appendix B describes future plans for the highway.

There were recurring topics addressed by the TCC over the years, and some of the major accomplishments are summarized on the following pages. Foremost always on residents’ minds was Alcoa highway. Opposition to commercial zoning expansion preoccupied early Alcoa efforts, but later agendas dealt more with safety – particularly after the highway was widened to four lanes. The background and history of the Alcoa highway development can be found in Section 6. Appendix B describes future plans for the highway.

Road Maintenance

Getting Knox County to keep the road patched, paved and painted required a generous level of attention from the Timberlake board members. The original base of 2-inch gravel was coated in 1951. Ten years later, the road was dangerously slick and in poor condition. For two years, 1960 through 1962, George Preston and Gordon Hunt repeatedly wrote the County, requesting the road be repaved and caution signs be installed. The road was finally recapped in 1964. Caution signs were erected and the center line repainted a year later. The road was resurfaced again in 1972, but once again it took a year to get the center line repainted.

Is it Timberlake Drive or Road?

Although the white street signs at the intersections at Montlake and Maloney say TIMBERLAKE RD., and many of the county property deeds prior to 1990 use “Road,” the street is officially recognized by Knox County and the U.S. Postal Service as Timberlake Drive. The earliest known reference found using “Drive” instead of “Road” is the Warranty Deed for the Rennie purchase of the 3715 property in 1971. While some residents have a nostalgic attachment to the unique white signs (and feel that “road” has a more befitting rural connotation than “drive”) standard green, reflective signs with “Drive” repeatedly have been requested from Knox County. Emergency responders rely on visible and accurate signage, so standardization is a safety issue… and will once again be pursued in 2010.

As a side note, there is no other Timberlake (Road, Drive, Lane, Avenue, Circle, Court, Boulevard or Street) in Knox County. However, in 2002 a Smithbuilt subdivision, “Harbor Cove at Timberlake,” was developed off Emory Road in the Halls area of north Knox County. Nearby Harbor Cove, Smithbilt is developing a second “Village of Timberlake” subdivision, featuring smaller single-family homes. Both Smithbilt developments have similarly designed, cookie-cutter style homes typical of most contemporary Knox County subdivisions.

Rezoning, Development and Annexation

From its earliest days, the Timberlake Community Club fought to protect the residential integrity of the neighborhood by preventing unwanted commercial and multi-family encroachment. Through an organized, unified voice—often in cooperation with other neighborhood organizations—the TCC was able to effectively communicate and occasionally even persuade Knox County government decision-making on issues that affected the character of the neighborhood and surrounding area. Without the vigilance of past leadership keeping an eye on rezoning requests, there likely would be rows of condominiums up and down Maloney Road with hundreds more cars sharing the narrow roads of Montlake, Ginn, Timberlake and Maloney. Alcoa highway would resemble every other corridor into the city, with commercial businesses lining its length from the UT Medical Center down to the county border at Topside Road.

As early as the 1950 organizational meetings, Timberlake residents were urged to join public opposition to commercial expansion on Alcoa highway. Heirs of the Hawkins land along the highway near Vernon Drive (entrance to Martha Washington Heights) had filed for rezoning of 1,500 feet of Alcoa frontage for commercial development. At the October 2, 1950, court hearing, 75 local residents showed up to stand against the change, with Timberlake representatives among them. This obstruction would be the first of many efforts, some successful and some not, by the Timberlake Community to keep the Alcoa corridor into the city free of commercial development.

In 1952, Dr. P.H. Cardwell owned (and still owns, as of 2009) residential property in the narrow hollow across from the Naval Amory/Training Center on Alcoa highway. Cardwell initially managed to get the property rezoned to allow construction of a grocery, restaurant and gift shop, assuring the commission that it would not be used for “any honky-tonks or beer joints.” Neighborhood opposition (from Woodson Road and Timberlake) pointed out that once it was rezoned, it could be used for any commercial establishment. The commission rescinded the zoning and noted neighborhood opposition, potential traffic hazards, and future widening of Alcoa as reasons.

The TCC picked its battles, and not all were fought without a cost. Wallace Ladd, a former resident of 3609 Timberlake and friend to many, owned property of eight acres at 3612 Maloney Road. Reportedly he was overwhelmed with the demands of lawn care, so he devised a plan to build approximately 40 condominiums on the land and filed for rezoning in March, 1983. The Timberlake community opposed the precedent-setting rezoning from agricultural to multi-family planned residential, feeling the land should be subdivided with single-family restrictions, and fearing that other large lakefront lots might be similarly used. Also in the spring of 1983, property owners Carolyn W. Huber and Mildred Irwin were seeking annexation by the city of Knoxville for their property on Alcoa Highway in order to get around county zoning restrictions. In these two cases, an attorney was retained to help represent and advise the neighborhood, and both initiatives were successfully blocked. Paying the resulting legal fees of $1,290 created a bit of a conundrum, in part because of collaboration with the Lakemoor Community Club. The fees ultimately were paid by requesting $50 per household from the Timberlake residents.

Generally, a positive spirit of cooperation with the Topside, Woodson, Martha Washington and Lakemoor communities benefited all the neighborhoods. One positive result in a futile search for area fire protection services was bringing the TCC together with other local neighborhood groups. The Topside neighborhood has been a long-time ally in Alcoa Highway planning issues dating back to the early 1950s and also during the 1970s when a sewage disposal plant site was proposed at the Cox Sky Ranch, south of the UT agricultural center. Another example of reciprocated cooperation was Timberlake’s backing of Martha Washington Heights’ opposition to a 1986 rezoning petition of a residential lot for the purpose of putting a restaurant at the entrance to their neighborhood. The Timberlake support was noted, in part, to be in response to Martha Washington residents’ support during the Ladd and Huber-Irwin issues from three years prior.

Not all development has been opposed, but good planning and smart development have been encouraged. In the case of the Village Shopping Center, Timberlake residents even offered to help with site planning. In another case, the Cove View Residence for the Elderly (a boarding house) was established on the corner of Maloney and Ginn in 1982. The home was fought by immediate neighbors, but was not officially opposed by the TCC. At least one Timberlake resident later lived her final years there.

Spot and “finger” annexations by the City of Knoxville have been an ongoing concern since the 1970s, posing a problem for non-annexed county property owners who lose representation about decisions affecting adjacent land. The failed “Gazebo at Waterford Cove” development near Maloney Road park, annexed by the city, was a recent case where county residents found themselves at the mercy of city commissioners when the developer attempted to alter the original plan from luxury condos to lower-cost apartments.

All in all, the legacy left by former Timberlake Community Club board members and politically-involved residents is a neighborhood that 60 years later retains its original appearance and single-family intent.

Fire Protection

For over 25 years, fire protection and emergency services were sought for the neighborhood. Early in the 1950s, the TCC had high expectations that the Chapman Highway Fire Dept. could expand coverage to the Alcoa/Topside area, but the department went bankrupt before a deal could be reached. Other suggestions considered and rejected (due to cost) included the addition of fire hydrants along Timberlake and installing a water tank somewhere at a higher elevation on the property.

Not everyone was particularly concerned about having tankers and pumping trucks within a few minutes of a roaring blaze, feeling sufficiently secure with the fire resistant nature of the block home construction and reasonable homeowner’s insurance rates, but the topic continued to come up, year after year. A private outfit called Federal Rescue Corps submitted a proposal for establishing service in the area in 1965, but the start-up costs proved too high. In 1969-70, options outside Knox County were investigated, including the Eagleton Village Fire Department near Maryville, and the Blount County Fire Department. Potential annexation by the City of Knoxville often complicated establishing any long-term solution because of the time required to recover start-up costs. In 1977 Knox County Consolidated Fire Department partnered with Rural Metro to offer coverage to the area, and – finally – the neighborhood had emergency services available.

Security

Throughout the years, occasional rashes of home burglaries and break-ins prompted the Timberlake Community Club to look into various home security methods. Common sense habits were frequently suggested, such as reminding folks about locking doors of homes and vehicles, not leaving keys in car ignitions, letting neighbors know when homes would be unoccupied during vacations or trips, and being alert for unfamiliar vehicles and people in the neighborhood. Some ideas were a little more inventive. In 1969, door decals saying “this house protected by radar burglar alarm” were offered (not an actual alarm; just a decal). A program called “Operation Identification” recommended in 1973 by the Knoxville News Sentinel suggested engraving social security numbers on valuables (an idea prior to the advent of identity theft). “Neighborhood Watch” signs were put up on both ends of Timberlake to warn potential intruders. Outdoor lighting and home burglar alarm systems were proposed for every home in the early 1970s, and much effort was put into researching available systems. Steel security doors, alarms, and motion-sensor systems monitored by ADT and other suppliers were installed in many homes.

The most elaborate neighborhood protection measure was an effort initiated by the Lakemoor Homeowners Association in 1977. The security plan included bonded and armed deputies, volunteer patrols, information centers equipped with CB radios, automobile I.D. decals, and a set of recommendations that seemed ambitious, if not a bit extreme. A few Timberlake residents participated in the volunteer patrols, but the program was eventually disbanded.

Changes to Charter Bylaws and Subdivision Restrictions

The Amended and Restated Bylaws of the Timberlake Community Club, Inc. are provided to all new property owners in the Timberlake Community Club. The Maloney Heights Subdivision Restrictions apply to the 44 lots within the original development. The Bylaws and Restrictions are reprinted in their entirety in appendix C.

The Timberlake Community Club Bylaws have been amended four times: Oct. 14, 1951 during the initial drafting process; May 29, 1986, to clarify voting status and remove gender-specific pronouns; and in October 1, 1998, and October 7, 1999, (following the Community lot disposition) to include membership of property owners outside the original Maloney Heights Subdivision.

There have been two changes to the Maloney Heights Subdivision Restrictions. In 1986 members voted to change paragraph 11, increasing the minimum ground area of a new home from 750 to 1500 square feet. The only change to the Subdivision Restrictions formally filed with Knox County register’s office was the deletion of Paragraph 12. It stated,

“No race or nationality other than Caucasian shall use or occupy any building on any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race or nationality employed by an owner or tenant.”

Although the paragraph was removed in February 1970, The Timberlake Community Club voted again to delete paragraph 12 at the annual business meeting in 1986. Due to past confusion about how, if, and when it was removed and due to continued interest about how the paragraph originally became included in the restrictions, following is an attempt to answer those questions based on historical context and information available in the TCC and Maloney Heights, Inc. files.

According to a notes from a preliminary organizational meeting of “Chapman Properties Group” in 1947, assignments for section seven, parts E: “Charter and by laws” and part F: “Bldg and land use restrictions” were given to Graves and Charles I. Barber. Notes taken during a March 1, 1948 meeting attended by Graves, Bowmaster, D.W. Barber, Hook, Crouch and Bob Young, state “…discussed and approved suggested restriction with corrections, and with minor additions to be developed by Young.”

It is not documented in notes or meeting minutes whether the restrictions Maloney Heights Inc. adopted were modeled after those for another local development or neighborhood. Thousands of neighborhoods throughout the country built before WWII and a few years after it, including the TVA town of Norris, had restrictions based on race. Racial covenants were not unique to southern states. Chicago and Seattle, for example, were nearly completely segregated through the use of such restrictions.

While racially restrictive covenants were determined by the Supreme Court (Shelley v. Kraemer) to be unenforceable as early as 1948, the original Maloney Heights Subdivision Restrictions remained unaltered and unmentioned in Community Club records until the late 1960s, when the Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act was upheld by the Court. (1968, Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co,). At the 1968 annual meeting, the minutes reflect that the by-laws of the TCC were read along with the MHI restrictions “to refresh our memories, and in case some of the new residents did not know them.” The restrictions were set to automatically extend for successive periods of ten years unless a majority of the owners agreed to change them.

The following year the revision was again discussed (documented in minutes, 11/20/1969), and Mary Elizabeth Witherspoon moved that paragraph 12 be deleted. Those present at the meeting unanimously agreed to delete the restriction, but there was not a quorum present. The board decided to study the process and arrange for a proper vote. On December 7, 1969, a new board of directors met, agreed that Supreme Court decisions had made the paragraph invalid, and felt it would be proper to delete it before the restrictions were automatically extended. Five days later, on December 12, 1969, a ballot and letter of explanation from the president (Dean Barber) was sent to all the TCC members.

A specific numeric tally of the vote was not documented, but a majority approved deletion, and amendment paperwork was filed with Knox County register’s office on February 20, 1970. In the 1970 annual business meeting minutes it was announced that paragraph 12 had been formally and legally removed from the Maloney Heights restrictions.

Maintaining Neighborhood Harmony

There are a few action items covered in the Timberlake Community Club annual meeting minutes that seem to be insignificant, almost humorously-described aggravations. Yet, even those seemingly minor issues had to be dealt with in an appropriate fashion. Following are a few examples where the board members and neighbors worked together to maintain neighborhood harmony.

Crisp Boat Dock

The peaceful summer of 1953 was rattled by “bootlegging, gambling, loud and boisterous conduct, immorality, shooting, and criminal hangers-on” at the Crisp Boat Dock on Maloney Road. (Crisp owned the land along Maloney Road directly north across the cove from Maxey’s Marina, now Waterford Cove condos.) The Knox County Beer Board had denied the dock owner a license, but he had continued to sell alcohol, attracting members of the Knoxville Boat Club. TCC president John H. Clark spearheaded efforts with other neighbors in the area to put and end to the night-time lawlessness. Through Clark’s persistent letters and phone calls to county and state officials, the illegal activities were permanently shut down.

Trees and Brush

Tree trimming and brush clearing was (and still is) a frequent topic at TCC meetings, with annual reminders to take care of low-hanging limbs or shrubs that created vehicular hazards. A county road crew occasionally comes through and uses a shredder to grind and tear the limbs back from the road edge; but, in the past, home owners were the primary caretakers responsible for keeping the roadway clear, (usually using a more careful pruning approach than the county crew). Neighborhood clean-up days were first initiated in the early 1950s and are still a springtime tradition

In the summer of 2008, the Knoxville Utility Board contracted a tree trimming crew that went on a month-long cutting spree, butchering and felling trees that had been in the neighborhood for decades in order to eliminate the canopy over the power lines. Through some spirited negotiation with KUB, a few particularly treasured trees are now marked with blue bands indicating a semi-protected status from future utility crews.

Garbage, Fences and Dogs

Herchel Macon noted in 1970 that he picked up “27 pieces of litter from along the roadside” in front of his property. Littering and dumping is not a major problem along Timberlake Drive, but the houses along Montlake and Maloney deal with fast food trash and beverage containers on a frequent basis—surprising, considering that the roads are mostly used by area residents. Clean-up crews were occasionally organized or hired to help maintain those areas.

Two rusted strands of barbed-wire stretch between 3301 and 3313 Timberlake. The fence was installed by Mrs. Woods in the 1990s to keep debris and junk, dumped by the owners of the next door property, from spilling into her yard. Other than that fence, representing a breakdown in communication between property owners, there are few in the neighborhood along side property boundaries other than those for safety or privacy around swimming pools or hot tubs. There are no subdivision restrictions regarding fencing, yet they are a rarity due to large wooded lots, the side lane right-of-way configuration, and a general reluctance to cordon off open spaces.

A consequence of fenceless yards, of course, has been the occasional free-roaming canine. Throughout the years there have been several beloved neighborhood dogs… and a few remembered not-so-fondly. While the neighborhood always has been welcoming of pets (including horses), the Timberlake Community Club board was pressed occasionally to deal with the sensitive task of chastising owners of aggressive dogs which were running loose and bothering walkers or joggers along the road. Knox county laws regarding pet restraint are quite clear and enforcement procedures harsh, but an announcement sent out on February 25, 1988, exemplified a tactful handling of such a situation in a local way that avoided a potentially angry confrontation or over-reaction. In recent years, electronic pet restraint systems have proven to be a successful technological tool in promoting goodwill between pets and neighbors.

The Timberlake Community Club files are filled with examples – in the meeting minutes, letters and announcements – which demonstrated rational leadership in resolving conflicts and tackling problems, no matter how small. When dealing with outside parties or county agencies, relentless persistence proved effective, while the often unheralded intermediary role of gentle self-governance proved to be a winning strategy for handling minor neighborhood disputes.

Children

For those new to the area, it’s somewhat surprising to learn that throughout most of Timberlake’s 60-year history, the neighborhood was abuzz with children. Of the 66 attending the first annual picnic in 1952, 24 were children. There were times when nearly every house on the road had kids living in it, with such an age range that social events planned activities for three age groups. As of October 2009, there are only four families with children in the home living in the Timberlake community. The demographic shift is partly due to “empty nests,” and partly due to westward sprawl in Knox County, resulting in perceived school district inequities that make the area less appealing for families with school-aged children. Timberlake elementary-aged children have attended Mount Olive Elementary since the beginning, carpooling until the school bus route changed to include Timberlake Road. High school students attended Young High School, then South-Young High until it was demolished in 1991 and merged with Doyle High.

For kids growing up in the neighborhood, it was, reportedly, an amazing place – especially before the area was fully developed. At first, party telephone lines were still in use, and there were few TV’s, so the great outdoors provided the primary entertainment. According to Margaret (Neilsen) Wayne, the Schenk/Akins front yard, one of the few level lots, was the softball field at 3613. Andrea Cain Wilson, an artist now living in Gatlinburg who grew up at 3722 Montlake, wrote “we had a wonderful area to live in and explore – river, forest, grasslands and orchards – what more could kids ask for?” Bob Bowmaster was in the third grade at Mount Olive Elementary when his family moved to Timberlake in 1949. He recalled the Lakemoor area to the north being mostly undeveloped in the early 1950s, providing a wilderness of hollows, hills, caves, and bluffs from Montlake all the way to the river.

There were still two active farms on Montlake (Jones and Cottrell) in the 1950s that provided manure for lawns and occasional work for the older boys. The original Peter Blow estate was boarded up during the early 1950s on the upper end of the peninsula, with just a couple houses in between it and Timberlake. Sissy (Prose) McMullen described riding their pony from their house on lot 29 (3510) around the ridge to the Johnson’s house, and playing along the spring-fed creek that runs through the gulley between the two houses. “Kids used to walk a long way to have fun,” she wrote. A cave somewhere along Maloney Road near the lake is now hidden by landscaping, but any child that grew up in the area could probably tell its location.

Lengthier accounts from children of Timberlake are included in Part II of the History Project. Hopefully, current residents will continue to reconnect with former “younger residents” to learn of and share their memories. The neighborhood history from their perspective is grand, poignant, fun, and full of fascinating interconnections among prior and later generations.

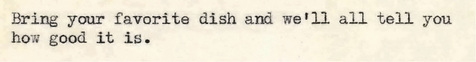

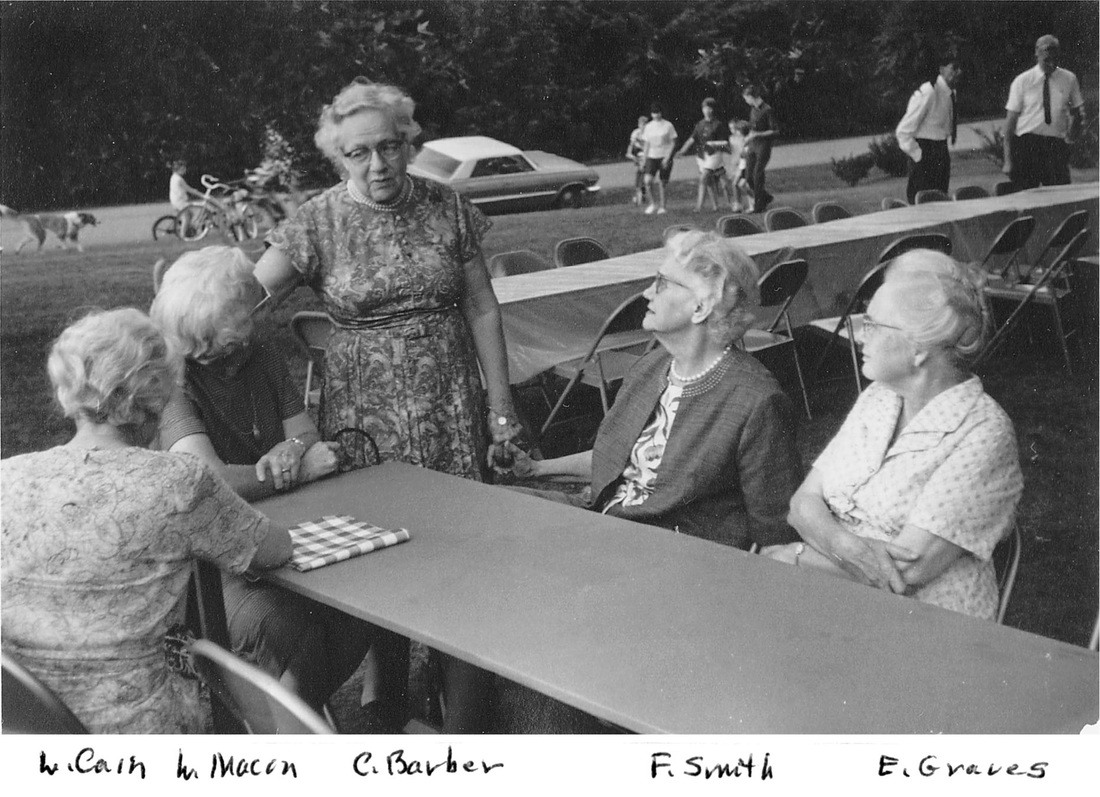

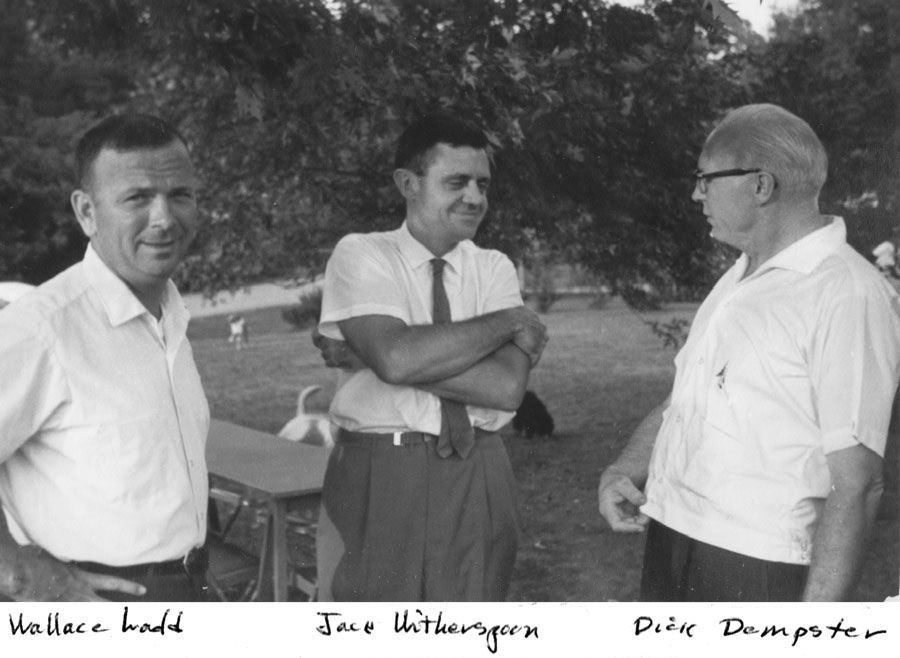

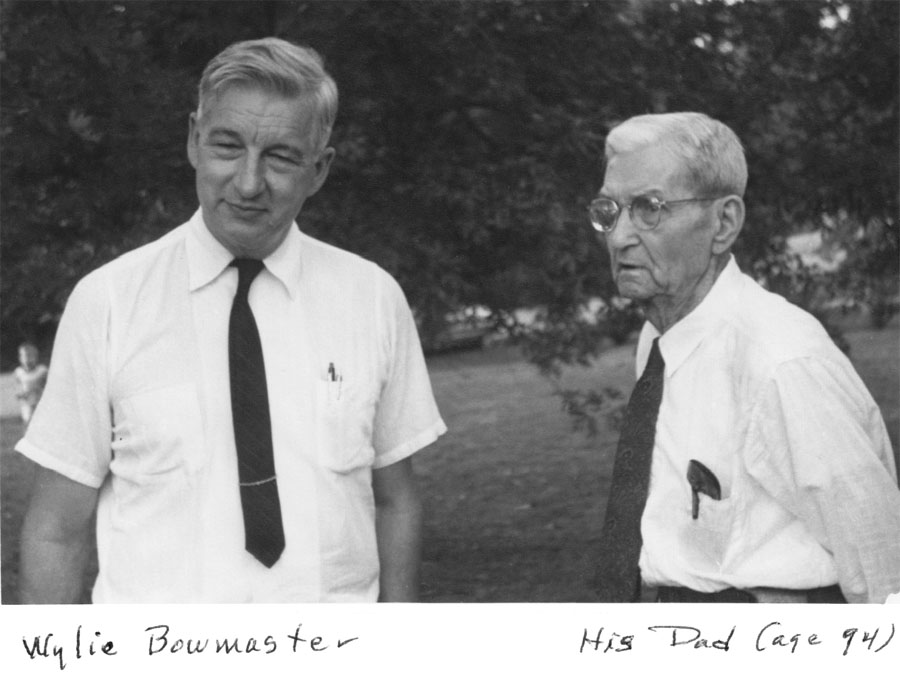

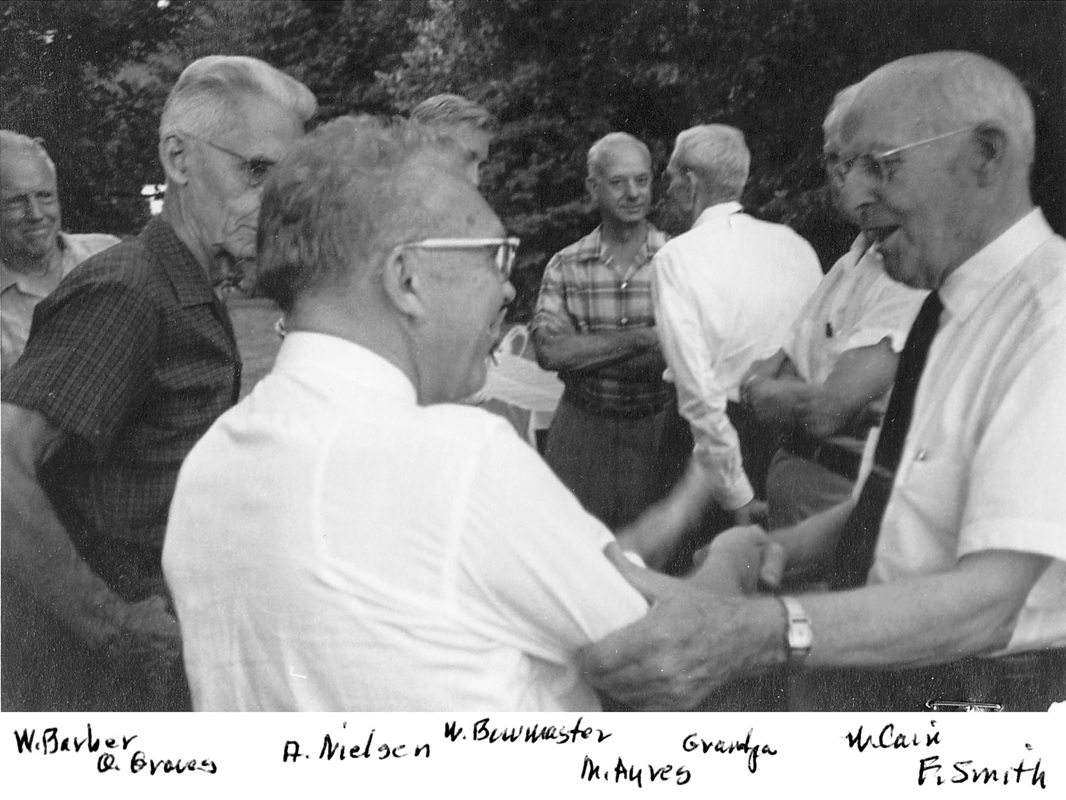

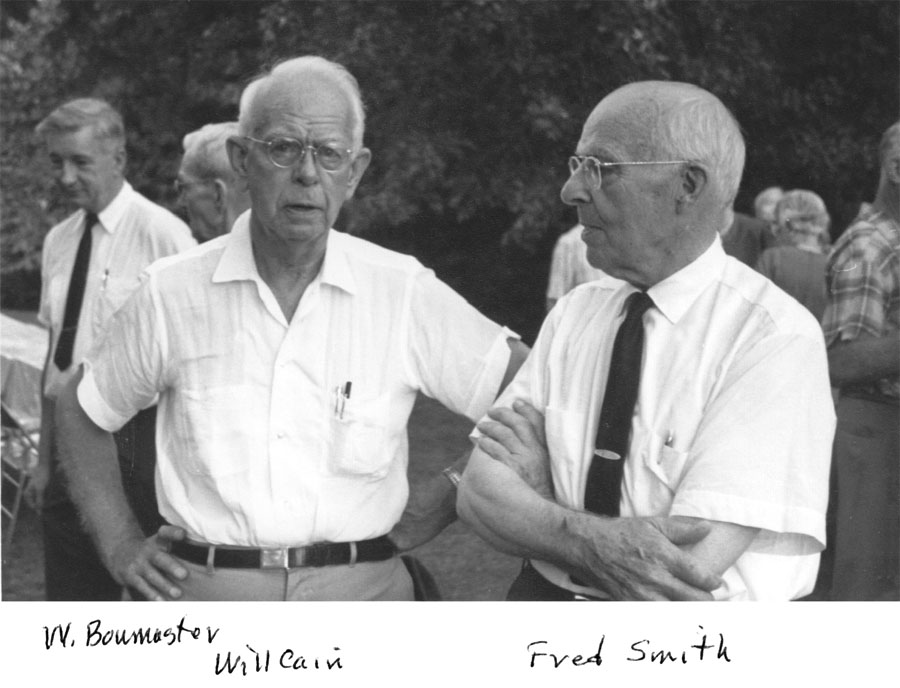

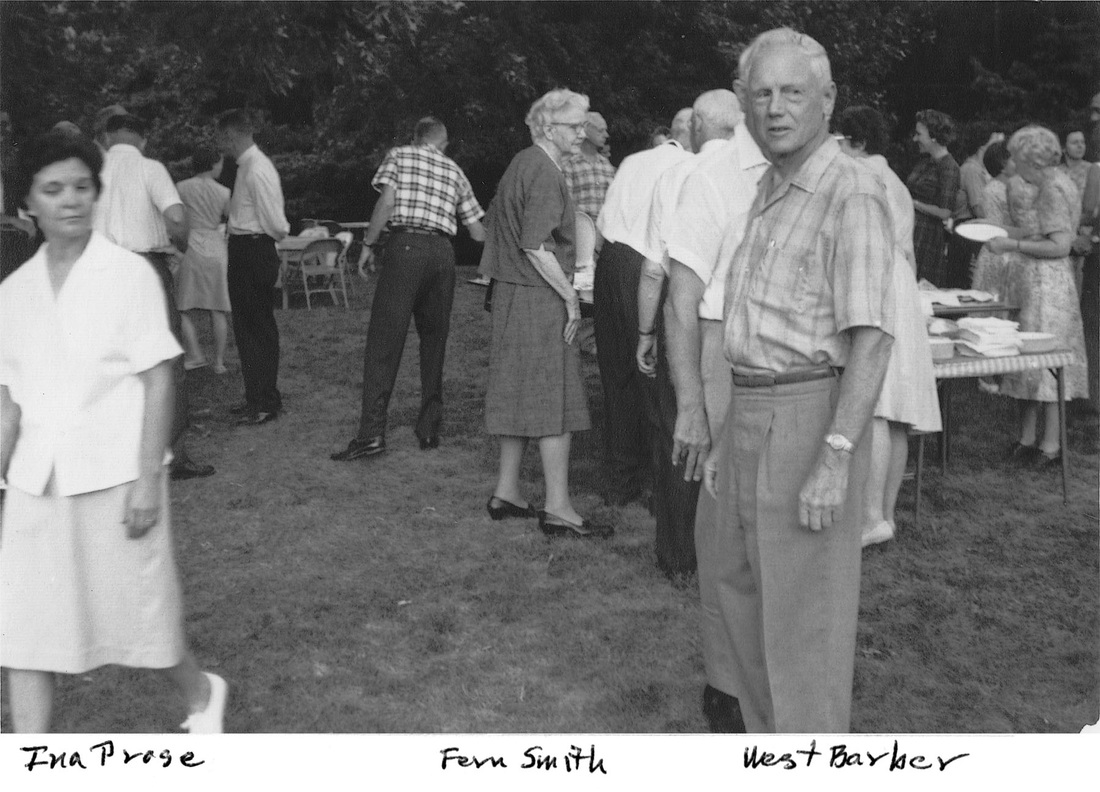

Photographs

Photos taken at the 1965 picnic on Homer and Virginia Johnson lawn at 3612 show many of the early residents who established the neighborhood. The pictures were filed with the Timberlake Community Club documents, and are included below with captions as originally written. The photographer is unknown (but greatly appreciated!). Click on photos to enlarge.

From its earliest days, the Timberlake Community Club fought to protect the residential integrity of the neighborhood by preventing unwanted commercial and multi-family encroachment. Through an organized, unified voice—often in cooperation with other neighborhood organizations—the TCC was able to effectively communicate and occasionally even persuade Knox County government decision-making on issues that affected the character of the neighborhood and surrounding area. Without the vigilance of past leadership keeping an eye on rezoning requests, there likely would be rows of condominiums up and down Maloney Road with hundreds more cars sharing the narrow roads of Montlake, Ginn, Timberlake and Maloney. Alcoa highway would resemble every other corridor into the city, with commercial businesses lining its length from the UT Medical Center down to the county border at Topside Road.

As early as the 1950 organizational meetings, Timberlake residents were urged to join public opposition to commercial expansion on Alcoa highway. Heirs of the Hawkins land along the highway near Vernon Drive (entrance to Martha Washington Heights) had filed for rezoning of 1,500 feet of Alcoa frontage for commercial development. At the October 2, 1950, court hearing, 75 local residents showed up to stand against the change, with Timberlake representatives among them. This obstruction would be the first of many efforts, some successful and some not, by the Timberlake Community to keep the Alcoa corridor into the city free of commercial development.

In 1952, Dr. P.H. Cardwell owned (and still owns, as of 2009) residential property in the narrow hollow across from the Naval Amory/Training Center on Alcoa highway. Cardwell initially managed to get the property rezoned to allow construction of a grocery, restaurant and gift shop, assuring the commission that it would not be used for “any honky-tonks or beer joints.” Neighborhood opposition (from Woodson Road and Timberlake) pointed out that once it was rezoned, it could be used for any commercial establishment. The commission rescinded the zoning and noted neighborhood opposition, potential traffic hazards, and future widening of Alcoa as reasons.

The TCC picked its battles, and not all were fought without a cost. Wallace Ladd, a former resident of 3609 Timberlake and friend to many, owned property of eight acres at 3612 Maloney Road. Reportedly he was overwhelmed with the demands of lawn care, so he devised a plan to build approximately 40 condominiums on the land and filed for rezoning in March, 1983. The Timberlake community opposed the precedent-setting rezoning from agricultural to multi-family planned residential, feeling the land should be subdivided with single-family restrictions, and fearing that other large lakefront lots might be similarly used. Also in the spring of 1983, property owners Carolyn W. Huber and Mildred Irwin were seeking annexation by the city of Knoxville for their property on Alcoa Highway in order to get around county zoning restrictions. In these two cases, an attorney was retained to help represent and advise the neighborhood, and both initiatives were successfully blocked. Paying the resulting legal fees of $1,290 created a bit of a conundrum, in part because of collaboration with the Lakemoor Community Club. The fees ultimately were paid by requesting $50 per household from the Timberlake residents.

Generally, a positive spirit of cooperation with the Topside, Woodson, Martha Washington and Lakemoor communities benefited all the neighborhoods. One positive result in a futile search for area fire protection services was bringing the TCC together with other local neighborhood groups. The Topside neighborhood has been a long-time ally in Alcoa Highway planning issues dating back to the early 1950s and also during the 1970s when a sewage disposal plant site was proposed at the Cox Sky Ranch, south of the UT agricultural center. Another example of reciprocated cooperation was Timberlake’s backing of Martha Washington Heights’ opposition to a 1986 rezoning petition of a residential lot for the purpose of putting a restaurant at the entrance to their neighborhood. The Timberlake support was noted, in part, to be in response to Martha Washington residents’ support during the Ladd and Huber-Irwin issues from three years prior.

Not all development has been opposed, but good planning and smart development have been encouraged. In the case of the Village Shopping Center, Timberlake residents even offered to help with site planning. In another case, the Cove View Residence for the Elderly (a boarding house) was established on the corner of Maloney and Ginn in 1982. The home was fought by immediate neighbors, but was not officially opposed by the TCC. At least one Timberlake resident later lived her final years there.

Spot and “finger” annexations by the City of Knoxville have been an ongoing concern since the 1970s, posing a problem for non-annexed county property owners who lose representation about decisions affecting adjacent land. The failed “Gazebo at Waterford Cove” development near Maloney Road park, annexed by the city, was a recent case where county residents found themselves at the mercy of city commissioners when the developer attempted to alter the original plan from luxury condos to lower-cost apartments.

All in all, the legacy left by former Timberlake Community Club board members and politically-involved residents is a neighborhood that 60 years later retains its original appearance and single-family intent.

Fire Protection

For over 25 years, fire protection and emergency services were sought for the neighborhood. Early in the 1950s, the TCC had high expectations that the Chapman Highway Fire Dept. could expand coverage to the Alcoa/Topside area, but the department went bankrupt before a deal could be reached. Other suggestions considered and rejected (due to cost) included the addition of fire hydrants along Timberlake and installing a water tank somewhere at a higher elevation on the property.

Not everyone was particularly concerned about having tankers and pumping trucks within a few minutes of a roaring blaze, feeling sufficiently secure with the fire resistant nature of the block home construction and reasonable homeowner’s insurance rates, but the topic continued to come up, year after year. A private outfit called Federal Rescue Corps submitted a proposal for establishing service in the area in 1965, but the start-up costs proved too high. In 1969-70, options outside Knox County were investigated, including the Eagleton Village Fire Department near Maryville, and the Blount County Fire Department. Potential annexation by the City of Knoxville often complicated establishing any long-term solution because of the time required to recover start-up costs. In 1977 Knox County Consolidated Fire Department partnered with Rural Metro to offer coverage to the area, and – finally – the neighborhood had emergency services available.

Security

Throughout the years, occasional rashes of home burglaries and break-ins prompted the Timberlake Community Club to look into various home security methods. Common sense habits were frequently suggested, such as reminding folks about locking doors of homes and vehicles, not leaving keys in car ignitions, letting neighbors know when homes would be unoccupied during vacations or trips, and being alert for unfamiliar vehicles and people in the neighborhood. Some ideas were a little more inventive. In 1969, door decals saying “this house protected by radar burglar alarm” were offered (not an actual alarm; just a decal). A program called “Operation Identification” recommended in 1973 by the Knoxville News Sentinel suggested engraving social security numbers on valuables (an idea prior to the advent of identity theft). “Neighborhood Watch” signs were put up on both ends of Timberlake to warn potential intruders. Outdoor lighting and home burglar alarm systems were proposed for every home in the early 1970s, and much effort was put into researching available systems. Steel security doors, alarms, and motion-sensor systems monitored by ADT and other suppliers were installed in many homes.

The most elaborate neighborhood protection measure was an effort initiated by the Lakemoor Homeowners Association in 1977. The security plan included bonded and armed deputies, volunteer patrols, information centers equipped with CB radios, automobile I.D. decals, and a set of recommendations that seemed ambitious, if not a bit extreme. A few Timberlake residents participated in the volunteer patrols, but the program was eventually disbanded.

Changes to Charter Bylaws and Subdivision Restrictions

The Amended and Restated Bylaws of the Timberlake Community Club, Inc. are provided to all new property owners in the Timberlake Community Club. The Maloney Heights Subdivision Restrictions apply to the 44 lots within the original development. The Bylaws and Restrictions are reprinted in their entirety in appendix C.

The Timberlake Community Club Bylaws have been amended four times: Oct. 14, 1951 during the initial drafting process; May 29, 1986, to clarify voting status and remove gender-specific pronouns; and in October 1, 1998, and October 7, 1999, (following the Community lot disposition) to include membership of property owners outside the original Maloney Heights Subdivision.

There have been two changes to the Maloney Heights Subdivision Restrictions. In 1986 members voted to change paragraph 11, increasing the minimum ground area of a new home from 750 to 1500 square feet. The only change to the Subdivision Restrictions formally filed with Knox County register’s office was the deletion of Paragraph 12. It stated,

“No race or nationality other than Caucasian shall use or occupy any building on any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race or nationality employed by an owner or tenant.”

Although the paragraph was removed in February 1970, The Timberlake Community Club voted again to delete paragraph 12 at the annual business meeting in 1986. Due to past confusion about how, if, and when it was removed and due to continued interest about how the paragraph originally became included in the restrictions, following is an attempt to answer those questions based on historical context and information available in the TCC and Maloney Heights, Inc. files.

According to a notes from a preliminary organizational meeting of “Chapman Properties Group” in 1947, assignments for section seven, parts E: “Charter and by laws” and part F: “Bldg and land use restrictions” were given to Graves and Charles I. Barber. Notes taken during a March 1, 1948 meeting attended by Graves, Bowmaster, D.W. Barber, Hook, Crouch and Bob Young, state “…discussed and approved suggested restriction with corrections, and with minor additions to be developed by Young.”

It is not documented in notes or meeting minutes whether the restrictions Maloney Heights Inc. adopted were modeled after those for another local development or neighborhood. Thousands of neighborhoods throughout the country built before WWII and a few years after it, including the TVA town of Norris, had restrictions based on race. Racial covenants were not unique to southern states. Chicago and Seattle, for example, were nearly completely segregated through the use of such restrictions.

While racially restrictive covenants were determined by the Supreme Court (Shelley v. Kraemer) to be unenforceable as early as 1948, the original Maloney Heights Subdivision Restrictions remained unaltered and unmentioned in Community Club records until the late 1960s, when the Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act was upheld by the Court. (1968, Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co,). At the 1968 annual meeting, the minutes reflect that the by-laws of the TCC were read along with the MHI restrictions “to refresh our memories, and in case some of the new residents did not know them.” The restrictions were set to automatically extend for successive periods of ten years unless a majority of the owners agreed to change them.

The following year the revision was again discussed (documented in minutes, 11/20/1969), and Mary Elizabeth Witherspoon moved that paragraph 12 be deleted. Those present at the meeting unanimously agreed to delete the restriction, but there was not a quorum present. The board decided to study the process and arrange for a proper vote. On December 7, 1969, a new board of directors met, agreed that Supreme Court decisions had made the paragraph invalid, and felt it would be proper to delete it before the restrictions were automatically extended. Five days later, on December 12, 1969, a ballot and letter of explanation from the president (Dean Barber) was sent to all the TCC members.

A specific numeric tally of the vote was not documented, but a majority approved deletion, and amendment paperwork was filed with Knox County register’s office on February 20, 1970. In the 1970 annual business meeting minutes it was announced that paragraph 12 had been formally and legally removed from the Maloney Heights restrictions.

Maintaining Neighborhood Harmony

There are a few action items covered in the Timberlake Community Club annual meeting minutes that seem to be insignificant, almost humorously-described aggravations. Yet, even those seemingly minor issues had to be dealt with in an appropriate fashion. Following are a few examples where the board members and neighbors worked together to maintain neighborhood harmony.

Crisp Boat Dock

The peaceful summer of 1953 was rattled by “bootlegging, gambling, loud and boisterous conduct, immorality, shooting, and criminal hangers-on” at the Crisp Boat Dock on Maloney Road. (Crisp owned the land along Maloney Road directly north across the cove from Maxey’s Marina, now Waterford Cove condos.) The Knox County Beer Board had denied the dock owner a license, but he had continued to sell alcohol, attracting members of the Knoxville Boat Club. TCC president John H. Clark spearheaded efforts with other neighbors in the area to put and end to the night-time lawlessness. Through Clark’s persistent letters and phone calls to county and state officials, the illegal activities were permanently shut down.

Trees and Brush

Tree trimming and brush clearing was (and still is) a frequent topic at TCC meetings, with annual reminders to take care of low-hanging limbs or shrubs that created vehicular hazards. A county road crew occasionally comes through and uses a shredder to grind and tear the limbs back from the road edge; but, in the past, home owners were the primary caretakers responsible for keeping the roadway clear, (usually using a more careful pruning approach than the county crew). Neighborhood clean-up days were first initiated in the early 1950s and are still a springtime tradition

In the summer of 2008, the Knoxville Utility Board contracted a tree trimming crew that went on a month-long cutting spree, butchering and felling trees that had been in the neighborhood for decades in order to eliminate the canopy over the power lines. Through some spirited negotiation with KUB, a few particularly treasured trees are now marked with blue bands indicating a semi-protected status from future utility crews.

Garbage, Fences and Dogs

Herchel Macon noted in 1970 that he picked up “27 pieces of litter from along the roadside” in front of his property. Littering and dumping is not a major problem along Timberlake Drive, but the houses along Montlake and Maloney deal with fast food trash and beverage containers on a frequent basis—surprising, considering that the roads are mostly used by area residents. Clean-up crews were occasionally organized or hired to help maintain those areas.

Two rusted strands of barbed-wire stretch between 3301 and 3313 Timberlake. The fence was installed by Mrs. Woods in the 1990s to keep debris and junk, dumped by the owners of the next door property, from spilling into her yard. Other than that fence, representing a breakdown in communication between property owners, there are few in the neighborhood along side property boundaries other than those for safety or privacy around swimming pools or hot tubs. There are no subdivision restrictions regarding fencing, yet they are a rarity due to large wooded lots, the side lane right-of-way configuration, and a general reluctance to cordon off open spaces.

A consequence of fenceless yards, of course, has been the occasional free-roaming canine. Throughout the years there have been several beloved neighborhood dogs… and a few remembered not-so-fondly. While the neighborhood always has been welcoming of pets (including horses), the Timberlake Community Club board was pressed occasionally to deal with the sensitive task of chastising owners of aggressive dogs which were running loose and bothering walkers or joggers along the road. Knox county laws regarding pet restraint are quite clear and enforcement procedures harsh, but an announcement sent out on February 25, 1988, exemplified a tactful handling of such a situation in a local way that avoided a potentially angry confrontation or over-reaction. In recent years, electronic pet restraint systems have proven to be a successful technological tool in promoting goodwill between pets and neighbors.

The Timberlake Community Club files are filled with examples – in the meeting minutes, letters and announcements – which demonstrated rational leadership in resolving conflicts and tackling problems, no matter how small. When dealing with outside parties or county agencies, relentless persistence proved effective, while the often unheralded intermediary role of gentle self-governance proved to be a winning strategy for handling minor neighborhood disputes.

Children

For those new to the area, it’s somewhat surprising to learn that throughout most of Timberlake’s 60-year history, the neighborhood was abuzz with children. Of the 66 attending the first annual picnic in 1952, 24 were children. There were times when nearly every house on the road had kids living in it, with such an age range that social events planned activities for three age groups. As of October 2009, there are only four families with children in the home living in the Timberlake community. The demographic shift is partly due to “empty nests,” and partly due to westward sprawl in Knox County, resulting in perceived school district inequities that make the area less appealing for families with school-aged children. Timberlake elementary-aged children have attended Mount Olive Elementary since the beginning, carpooling until the school bus route changed to include Timberlake Road. High school students attended Young High School, then South-Young High until it was demolished in 1991 and merged with Doyle High.

For kids growing up in the neighborhood, it was, reportedly, an amazing place – especially before the area was fully developed. At first, party telephone lines were still in use, and there were few TV’s, so the great outdoors provided the primary entertainment. According to Margaret (Neilsen) Wayne, the Schenk/Akins front yard, one of the few level lots, was the softball field at 3613. Andrea Cain Wilson, an artist now living in Gatlinburg who grew up at 3722 Montlake, wrote “we had a wonderful area to live in and explore – river, forest, grasslands and orchards – what more could kids ask for?” Bob Bowmaster was in the third grade at Mount Olive Elementary when his family moved to Timberlake in 1949. He recalled the Lakemoor area to the north being mostly undeveloped in the early 1950s, providing a wilderness of hollows, hills, caves, and bluffs from Montlake all the way to the river.

There were still two active farms on Montlake (Jones and Cottrell) in the 1950s that provided manure for lawns and occasional work for the older boys. The original Peter Blow estate was boarded up during the early 1950s on the upper end of the peninsula, with just a couple houses in between it and Timberlake. Sissy (Prose) McMullen described riding their pony from their house on lot 29 (3510) around the ridge to the Johnson’s house, and playing along the spring-fed creek that runs through the gulley between the two houses. “Kids used to walk a long way to have fun,” she wrote. A cave somewhere along Maloney Road near the lake is now hidden by landscaping, but any child that grew up in the area could probably tell its location.

Lengthier accounts from children of Timberlake are included in Part II of the History Project. Hopefully, current residents will continue to reconnect with former “younger residents” to learn of and share their memories. The neighborhood history from their perspective is grand, poignant, fun, and full of fascinating interconnections among prior and later generations.

Photographs

Photos taken at the 1965 picnic on Homer and Virginia Johnson lawn at 3612 show many of the early residents who established the neighborhood. The pictures were filed with the Timberlake Community Club documents, and are included below with captions as originally written. The photographer is unknown (but greatly appreciated!). Click on photos to enlarge.